Still Standing: Artist Victor Ehikhamenor’s Response to the Monument to Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson by the Army and Navy Company of Regent Street

About the Artwork

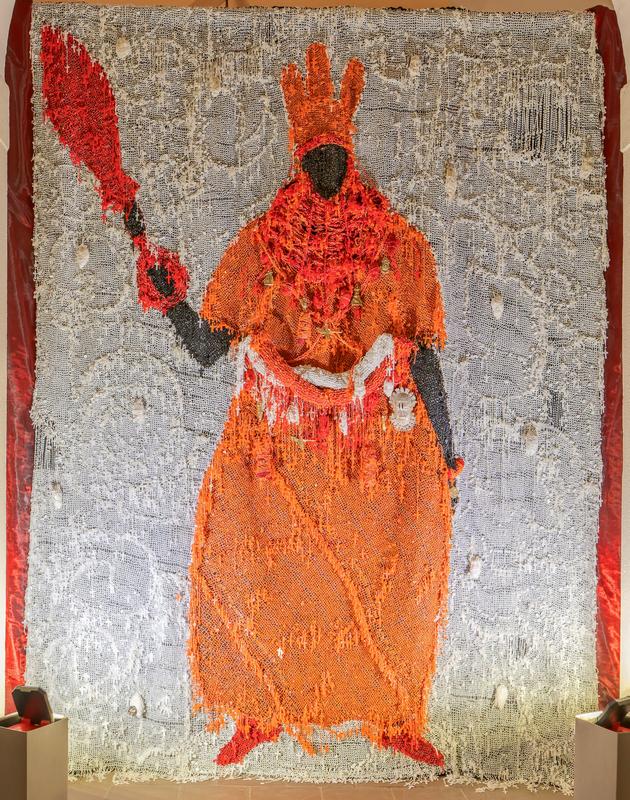

Still Standing is a new work in artist Victor Ehikhamenor’s series of multimedia ‘Rosary Works‘, which incorporate symbols from both Edo religion and Catholicism, reflecting on the confluence of African and Western cultures. Still Standing combines Benin bronze hip ornament masks with thousands of rosary beads to depict an Oba (King) of Benin.

Still Standing responds to a brass memorial panel to Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson (1843-1910) installed in the Nelson Chamber of the Cathedral’s Crypt in 1913. As the panel notes, Rawson had a long career in the Royal Navy, which culminated in his commanding the Benin Expedition of 1897. Still Standing was installed next to the monument on the eve of the 125th anniversary of the sacking of Benin City on 18 February 1897. It poses questions about art, commemoration, ancestry, and reconciliation in the aftermath of colonial war.

History never sleeps nor slumber. For me to be responding to the memorial brass of Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson who led British troops in the sacking of Benin Kingdom 125 years ago is a testament to this. The installation Still Standing was inspired by the resolute Oba Ovonramwen who was the reigning king of Benin Kingdom at the time of the expedition, but the artwork also memorializes the citizens and unknown gallant Benin soldiers who lost their lives in 1897 as well as the vibrant continuity of the kingdom till this day. I hope we the descendants of innumerable uncomfortable thorny pasts will begin to have a meaningful and balanced conversations with projects like 50 Monuments in 50 Voices.

Victor Ehikhamenor

Still Standing was specially commissioned for this installation at St Paul’s as part of the 50 Monuments in 50 Voices project, with generous support from Art Fund. It was curated by Dan Hicks (Professor of Contemporary Archaeology at University of Oxford and Curator at the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum) and Simon Carter (Head of Collections, St Paul’s Cathedral) .

Still Standing has been acquired by the Pitt Rivers Museum, which holds one of the most significant collections of Benin royal artworks looted in 1897. It can be viewed at St Paul’s until 14 May 2022.

About Viktor Ehikhamenor

Viktor Ehikhamenor is a Nigerian multimedia artist, photographer, and writer. He has been prolific in producing abstract, symbolic, and politically/historically motivated works. Ehikhamenor’s work employs unexpected techniques of making and unmaking, of building images and shapes, and/or constructing figurative works from complex, illegible ancient scripts, tears and holes, and Catholic symbols, to create portraits of African people and depict African spaces. Using materials and iconography that embrace the traditions and histories of Africa while integrating elements that allude to the continent’s colonial past and Nigeria’s complex geopolitical position as an oil-producing nation, the scenes and figures depicted are often figurative and a mix of symbols that straddle his Benin Kingdom traditions and Catholic upbringing. This duality builds narratives that comment on the complex cultural and political reality of Nigerians in their private and public lives, both historically and today.

A 2020 National Artist in Residence at the Neon Museum, Las Vegas, Nevada, Ehikhamenor is also a 2016 Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Fellow. He has held several solo exhibitions and his works have been included in numerous group exhibitions and biennales, including The 57th Venice Biennale as part of the Nigerian Pavilion (2017), 5th Mediations Biennale in Poznan, Poland (2016), The 12th Dak’art Biennale in Dakar, Senegal (2016), and the Biennale Jogja XIII, Indonesia (2015).

As a writer, he has published fiction and critical essays with academic journals, magazines, and newspapers around the world including New York Times, Guernica Magazine, BBC, CNN Online, and Washington Post

Ehikhamenor is the founder of Angels and Muse, a thought laboratory dedicated to the promotion and development of contemporary African art and literature in Lagos, Nigeria.

Visit Ehikhamenor’s website and find him on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

About the Monument

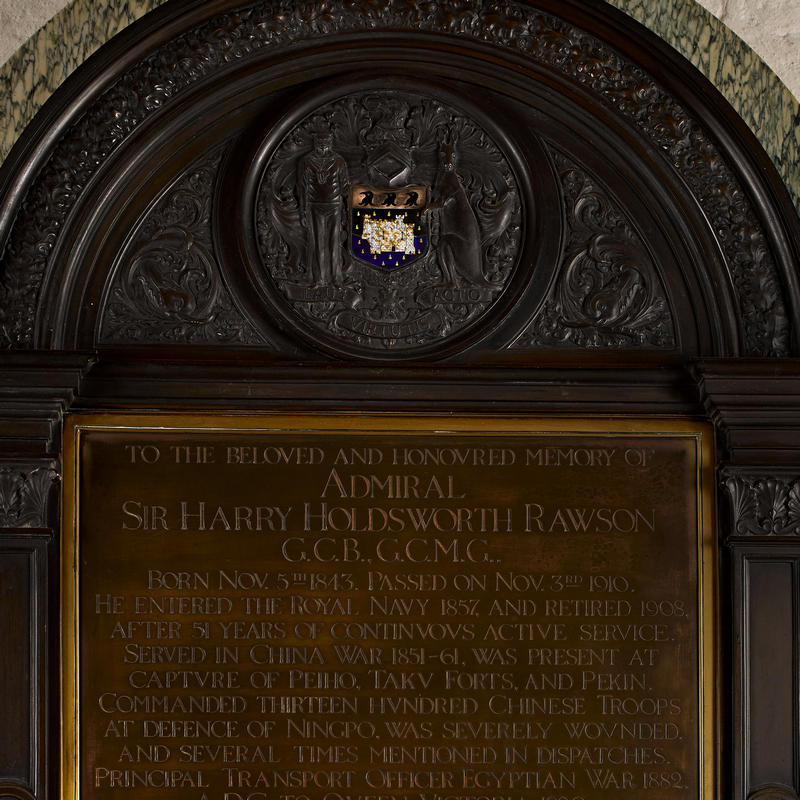

The Army and Navy Company of Regent Street’s c. 1912–1913 bronze, marble, and brass memorial panel to Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson (1843–1910) can be found in the east aisle of the Nelson Chamber in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. Examined closely, its complex iconography includes English oak leaves and acorns, raven heads, Arabic script, a fort with a moat, Corinthian pilasters, dolphins, the Royal Humane Society silver medal, a naval officer, and a kangaroo, indicating Rawson’s last post as Governor of New South Wales.

It details Rawson’s involvement in some of the most controversial military campaigns of the nineteenth century, including the Second Opium War in China and the destruction of Benin City in Benin in February 1897. Rawson was in charge of the forces responsible for the bombardment and looting of Benin city, in what is now southern Nigeria, a murderous campaign involving many millions of British bullets. The spoils, including thousands of bronze plaques and carved ivory tusks depicting the history of the Benin Royal Court, were subsequently gifted to Queen Victoria and the British Museum and purchased for the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. Their contemporary presence in these European collections remains highly controversial.

Video Transcript

Can you tell us about the artwork and what inspired it?

The piece is titled Still Standing and first of all, that title is gotten from the fact that the Benin Kingdom, which was part of a huge inspiration for creating the work, is still standing. Because there’s a lot of people that are of the opinion that it’s a past culture. It’s very present; it’s very current; it’s a living culture. So that’s where the title comes from.

And also the title comes from the Oba Ovonramwen who was in power when the British soldiers attacked the kingdom. So mainly, he’s still standing, his story’s still standing, and he’s still very much in commemoration.

What do you want people who see this artwork to experience?

I think people will come here with their different readings, different backgrounds, and different meanings to it, you know. So it’s very, it’s kind of, not one of those that prescribe to people how they should read my work or how they should see my work. But I think I’m hoping that it will open up a lot of conversations.

It will also, like, point people to a direction that they were not looking before, to look at, okay, contemporary art, that is coming out from Africa,

coming out from Nigeria, coming out from Edo State, coming out from Benin City – and how is that in conversation with what is happening globally,

as well as what is happening in London or England in particular, you know.

So, and especially in the whole conversation about restitution, I hope that this kind of leads people and holds their hand into it as much as possible.

Can you tell us a little bit about some of the cultural references in the artwork?

So this is heavily influenced by the way a king, the Oba of Benin, would normally dress, you know. So whereas I’m using rosary beads, which is that duality and kind of fusing two cultures together, this part of the pieces, the sarong and the dressing of the king would be made out of coral beads – which are kind of the traditional ways of making them, you know. And we also have to realise that coral beads were imported into Benin from Portugal, or had dealings with Portuguese, but it has become part of the culture. So now I’m using rosaries, you understand, you know, so, to create that kind of aesthetic scenario.