Marble Anthem: Composer Patrick John Jones’ Response to the Monument to Sir John Stainer (1840–1901) by Henry Pegram, 1903

For a brief description of the way Marble Anthem works, please read the listening guide directly below. More detailed background is provided in the subsequent section: ‘I Am Sitting in a Cathedral’.

Marble Anthem – Listening Guide

In Marble Anthem, John Stainer’s choral work ‘I saw the Lord’ (1858) is heard in its entirety but for the most part it is transformed beyond recognition. First, it gradually becomes buried within the acoustic of the nave of St Paul’s Cathedral, then it drifts upwards to the acoustic of the much smaller library on the floor above ‘borne aloft on smoke and flames’, and finally it returns to the nave to rapidly emerge from its subsumed state for the final ‘Amen’. The following timestamps will help you to orientate yourself within this process:

0:07

The Stainer anthem dissolves as it is replaced by the characteristic resonant frequencies of the nave. A visual metaphor might help to illuminate this process: imagine zooming out from the monument so that it gets smaller and smaller whilst more of the cathedral’s majestic interior is revealed.

2:15

The ‘zooming out’ ends here. Nothing resembling a human voice can be recognised at this stage.

2:47

The process of moving up to the library begins.

3:43

The music has now fully moved into the library, accompanied by the sounds of fire and smoke. The Stainer is less ‘buried’ here, and so the occasional angelic voice emerges from the smoke. This is an unsettlingly dissonant effect, as the resonant frequencies of the room clash with those of the Stainer anthem.

6:07

The music begins to move back to the nave.

6:39

Once the music has fully moved from the library back to the nave, the initial dissolving process is rapidly reversed as the music approaches the final ‘Amen’.

‘I Am Sitting in a Cathedral’

Pegram’s marble mural evokes ‘I saw the Lord’ (1858), John Stainer’s most famous choral composition, by depicting its most visually striking lines. In the upper section is a representation of Christ seated on a throne (‘I saw the Lord, sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up’), surrounded by winged angels’ heads (‘Above it stood the seraphims: each one had six wings’) borne aloft on smoke and flames (‘the house was filled with smoke’). My ‘sonic monument’ is therefore a response to a response – the end point of a journey from sound to marble and back to sound.

Aside from the direct connections to Pegram’s monument in Marble Anthem – the appropriation of Stainer’s music and the mingling of fire and smoke with angelic voices – I also wanted to represent the idea of space in the music. All the artefacts in the 50 Monuments in 50 Voices project are to some extent defined by the space they are in as well as what they are. You find them by moving around the vast interior of the cathedral, seeing them at a distance, up close, from different angles, emerging from behind pillars, and so on. Part of what makes them interesting is the way they relate to the form and material of St Paul’s itself as well as the way they relate to each other.

To address this, I drew inspiration from I am sitting in a room (1969), a piece of sound art by the experimental composer Alvin Lucier. The composer made this work by recording himself narrating a text whilst sitting in a room, playing the tape recording back into the same room, re-recording it, then repeating the re-recording process over and over again with each successive new recording. Gradually his words disappear, replaced by the sound of the characteristic resonant frequencies of the room. His own text describes the process:

‘I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.’

Alvin Lucier

Replicating I am sitting in a room in one of London’s busiest cathedrals comes with some obvious logistical complications. I had three hours to play with in an empty St. Paul’s, and whilst it would have been just about possible to recreate the Lucier in that time, it would have been a close call. On top of this, I wanted to experiment with the process in other spaces in the building, aside from just the nave, which was definitely not possible in the given time. This led me to recruit the help of the team behind the Open Acoustic Impulse Response Library (or OpenAIR) based at the University of York.

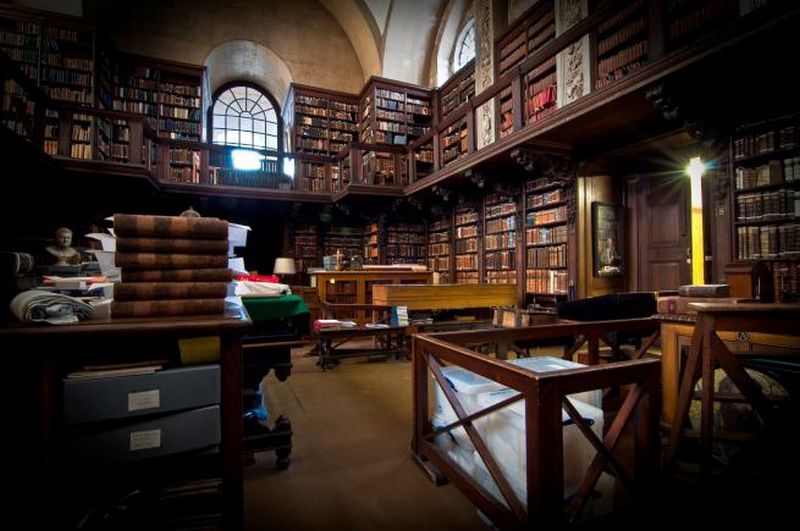

OpenAIR is a project that is dedicated to gathering data about the acoustics of different spaces around the world, including a nuclear reactor in Stockholm and a neolithic tomb in County Meath, Ireland. This data is captured by recording something called an ‘impulse response’ and can be used to digitally apply the reverberation of a certain space to an existing recording. For instance, if you were to record yourself saying something right now, wherever you happen to be, you could listen back to the recording as if it had been recorded in a neolithic tomb or nuclear reactor. Or, more importantly, in St Paul’s Cathedral. In three hours, the OpenAIR team recorded impulse responses in the nave, quire, Geometric Staircase, library, and Whispering Gallery.

All these impulse response recordings will be made available on the OpenAIR Library website. Marble Anthem uses those from the nave and library. The nave’s acoustic is expansive and more fitting for the music. (In fact, it may suit the acoustic so well because Stainer allegedly wrote it for the cathedral. The story is unattributed but believable, as Stainer was a young chorister at the St. Paul’s – surely this would have had a formative effect on his experience of choral music.) The library is a much smaller space, and the prominent frequencies of its acoustic are dissonant in relation to the tonality of the Stainer. These properties enable a simple structural trajectory from consonance (in the nave) to dissonance (in the library) and back to consonance.

Acknowledgements

Marble Anthem uses the St Paul’s Cathedral Choir’s 1989 recording of ‘I Saw the Lord’ released on Hyperion records, conducted by John Scott and with Andrew Lucas playing the organ.

The impulse response recordings were made on 25th August 2022 by members of the OpenAIR project at the University of York: Professor Damian Murphy, Dr Aglaia Foteinou and Dr Frank Stevens.

This work forms part of Patrick John Jones’s Early Career Fellowship project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

Marble Anthem, Listening Notes and ‘I Am Sitting in a Cathedral’ © Patrick John Jones 2022

About Patrick John Jones

Dr Patrick John Jones is a composer and researcher currently working on a practice-based Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship at Guildhall School of Music & Drama. His project – ‘Sounding the archive: composition as translation and adaptation’ – aims to build a bridge between artistic practice-based research and intermedial theory through the composition of original music that interacts with sources from archives, galleries, and museums. It will also explore the public engagement potential of elucidating such interactions to facilitate broader understanding of, and interaction with, contemporary classical music.

Patrick’s music has been described as ‘strange, eerie…expressive’ (Britten Sinfonia Blog), ‘assured…compelling’ (Bachtrack), ‘acerbic’ (The Guardian) and ‘remarkably fresh’ (The Philharmonia Blog). It has been performed by artists and ensembles such us the London Symphony Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Ensemble 10/10, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Quatuor Diotima, Mahan Esfahani, The Kreutzer Quartet, Octandre, Psappha, the Tritium Trio, the Berkeley Ensemble, and the Ulysses Ensemble.

Patrick was a joint winner of the Calefax Composers Competition in 2020. He received the RPS Composition Prize in 2015, and the Britten Sinfonia’s OPUS award in 2014.

His piece for mixed quartet The Fun Will Never End was recorded by the London Symphony Orchestra and released on NMC in 2021 on the Six Degrees of Separation compilation. Some of his scores have been published by the University of York Music Press, including Prayer (1) for soprano, alto and male voice (2020) and Uhtceare for flute, percussion, violin and cello (2016). Uhtceare was also recorded and released as part of the Dark Inventions album ‘Firewheel’ in 2016.

For a full bio, visit Patrick’s institutional profile.

About the Monument

Sir John Stainer (1840–1901) was both a boy chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral and, from 1872–1888, the Cathedral organist. His time as organist was a period of reform for the choir, which gained the high reputation it has to this day. Stainer’s oratorio The Crucifixion is perhaps his most famous choral composition today but it is the opening words (and title) of his two-choir anthem ‘I Saw the Lord’ that are proclaimed on his wall-panel monument by Henry Alfred Pegram RA (1862–1937). The quotation from Isaiah 6 also inspired the relief imagery above Stainer’s roundel portrait, which shows the prophet Isaiah, arms raised as he beholds the vision rising from his altar, of Christ enthroned surrounded by singing cherubim and with the Holy Spirit descending in the form of a dove.