Chair of the BMA Council, Dr Chaand Nagpaul’s Response to the Monument to Dr William Babington (1756–1833), by William Behnes, 1837

Transcript

By Dr Chaand Nagpaul

In 1777, in the King’s House, Winchester, built by Christopher Wren and modelled after the Palace of Versailles, Dr William Babington cared for French and Spanish sailors taken as prisoners of the American War of Independence.

Hundreds captured from their ships the Pallas and the Licorne by Admiral Keppel were crowded in and sick with fever, smallpox, and other disease. Babington’s diligent efforts almost cost him his own life after being stricken with typhus and only narrowly surviving. At this hospital surrounded by militia his efforts were not unnoticed. Many who were sick recovered, and very few died.

Babington had come from Ireland and was raised in County Antrim, apprenticed in Londonderry, and finished his education at Guy’s Hospital. His excursion to Winchester ended when he was recalled to London and to Guy’s to take on the role of apothecary. He qualified in 1795, and by 1810 he was recognised as the leading physician in London.

He sought out the hard edges of society. Never retiring from medicine, he offered his services to the poorest in a city rife with poverty and disease. This was the London of Jacob’s Island and the Old Nichol, and the Devil’s Acre and Agar Town, shanty and slum and squalid tenement, insecure from age and decay, humans blighted by brutal industry.

In February 1833, London was met by a punctilious rain; in March it was harassed by an influenza epidemic. On the 24th of April, in great personal distress, and weakened by fever, he continued to visit his patients until late in the evening. The next morning he was delirious, and Babington died like the people he treated.

Contemporaries eulogised his ancient manners, eminent reputation and rare benevolence. One remarked that he put nothing on record that will long survive him.

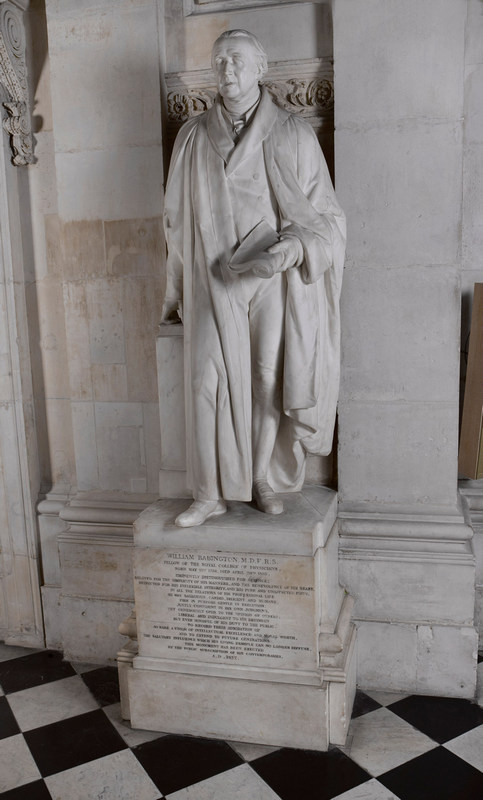

In this pantheon of St Paul’s, surrounded by military might, and the countenances of saints, why build a monument to a man whose work did not venture into the field of original discovery?

It is the nature of medicine to pursue a dual purpose. The scientific advancements necessary to prevent, alleviate or cure illness, and the professional integrities and virtues that inspire trust, compassion, and respect for human life. Dr Richard Bright, in his eulogy at the College of Physicians, described Babington’s personal sacrifice of the great scientific discovery in favour of the “exemplary execution of the professional ideal”.

His acts of kindness, embodied in his individual encounters with the sick and the poor – and not his toil towards a universal scientific discovery – were cause for this memorial statue in dedication to his bright example. These virtues have not been lost in the ruptures of history or by a changing social contract but remain immanent to the medical profession. It was, of course, the same values which led to that revolutionary moment of the creation of the National Health Service.

The sad parallels we can draw between the influenza endemic of 1833, which took Babington’s life, and the pandemic of 2020, reflect the depths of courage and bravery of the medical profession and these enduring values. With no guarantee of personal safety, amidst shortages of protective equipment, with no vaccination or effective therapeutics, doctors made their sacrifices to continue to heal the sick. It is a cruel tragedy that in saving the lives of tens of thousands of patients, so many doctors lost their own.

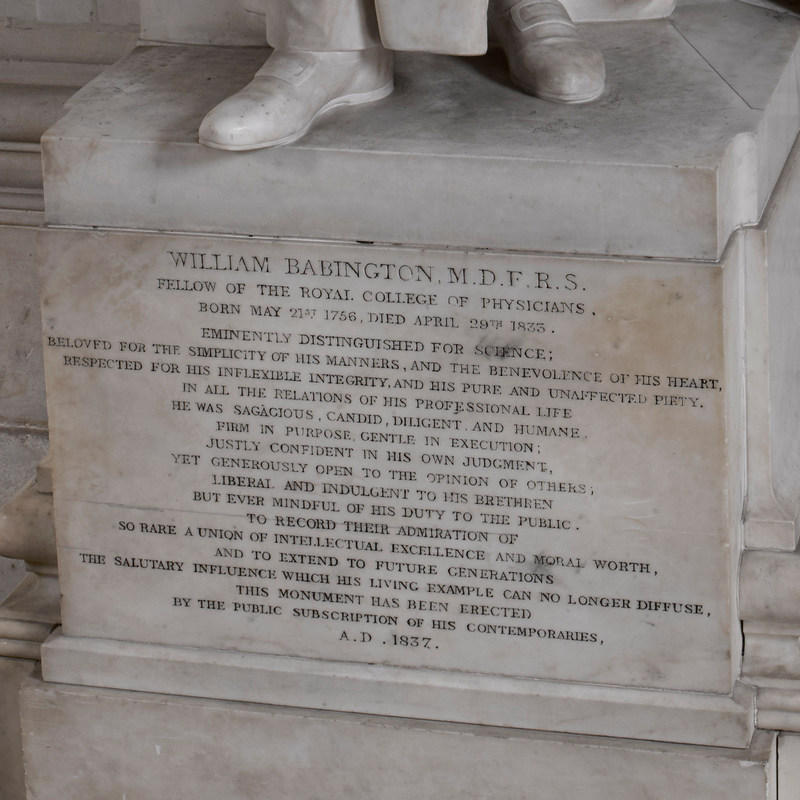

This common sentiment, between 1833 and today, between Babington and my colleagues, between his virtue – and theirs – finds expression in this statue, in its graceful lustre, and in its inscription carved into marble about his character:

So rare a union of intellectual excellence and moral worth to extend to future generations.

From the depths of this recent tragedy, these words do not simply define Babington but define his profession. Their meaning renewed by the individual and the collective acts of doctors today, in service to the people of this nation.

About Dr Chaand Nagpaul

Dr Chaand Nagpaul has for over three decades worked as a GP in his group practice in North London, serving a large multi-ethnic community.

He is the first BAME chair of the British Medical Association (BMA) council, representing the medical profession across the UK to government and policy makers. As BMA council chair, he has championed race equality in the NHS. He has been a visible figure calling for action to address the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on BAME healthcare workers and communities and gave evidence on this issue to Parliamentary committees and contributed to Baroness Lawrence’s review ‘An Avoidable Crisis‘.

He is listed in Health Service Journal‘s 50 most influential BAME people in health (2020).

He is past chair of the BMA GPs committee (GPC) and a Fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners.

Chaand was awarded a CBE in 2015 for his services to primary care.

Find Chaand on Twitter.

About the Monument

The monument to Dr William Babington (1756–1833) is located in the south transept on the main floor of St Paul’s Cathedral. It is considered a masterpiece of the sculptor William Behnes (1795–1864), who, in the same year that the Babington monument was unveiled (1837), became ‘Sculptor in Ordinary’ to Queen Victoria.

The full inscription, to which Dr Chaand Nagpaul alludes in his Voice, reads:

WILLIAM BABINGTON, M.D. F.R.S.

Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians,

born May 21st.1756, died April 29th.1833.

Eminently distinguished for science;

beloved for the simplicity of his manners, and the benevolence of his heart,

respected for his inflexible integrity, and his pure and unaffected piety.

In all the relations of his professional life

he was sagacious, candid, diligent, and humane.

Firm in purpose, gentle in execution;

justly confident in his own judgement,

yet generously open to the opinion of others;

liberal and indulgent to his brethren

but ever mindful of his duty to the public.

To record their admiration of

so rare a union of intellectual excellence and moral worth,

and to extend to future generations

the salutary influence which his living example can no longer diffuse,

this monument has been erected

by the public subscription of his contemporaries,

A.D.1837.

Image credits

The video contains the following images:

- An East View of the King’s House at Winchester…, British Library, public domain.

- Frontispiece showing Guy’s Hospital, from A syllabus of a course of chemical lectures read at Guy’s Hospital, by William Babington and William Allen (1802), Wellcome Collection, public domain.

- ‘Old Houses in London Street, Dockhead about 1810’, from Old and New London : A Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places, by Walter Thornbury (), Wellcome Collection, public domain.

- ‘Lodging House in Field Lane’, from Sanitary ramblings. Being sketches and illustrations of Bethnal Green. A type of the condition of the Metropolis and other large towns, by Hector Gavin (1848), Wellcome Collection, public domain.

- ‘Wentworth St, Whitechapel’, from London: A Pilgrimage, by Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold (1872). Print made by Antoine Valérie Bertrand after Gustave Doré, 1872, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum, (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

- William Babbington M.D.F.R.S., print made by William Thomas Fry after James Tannock, 1831–1840, published by Leggatt Bros, London, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum, (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).