‘Thinking about Colour: Turner, Temeraire and Turning Tides’: Cultural Historian, Broadcaster and Author Janina Ramirez’s Response to the Monument to J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851) by Patrick MacDowell RA (c. 1851–1855)

Thinking about Colour: Turner, Temeraire and Turning Tides – Transcript

by Janina Ramirez

St Paul’s Cathedral is a Baroque masterpiece. But whenever I cast my eyes across the perfectly sculpted marble faces of the great men whose memorials line its edges, something, for me, is missing – colour, at least on the Cathedral floor. That’s the medievalist in me; I’m more at home in a Gothic edifice jammed with busy wall paintings, lit by a kaleidoscope of colour filtered through stained glass. Wren’s masterpiece and the best known sculptures that live eternally inside it are from another world: the classical tradition. Here monuments and the people they represent are perpetuated in white marble, set forever in stone, classicised and idealised.

This was, of course, deliberate. When Wren crafted his masterpiece to rise from the ashes of the Great Fire of London, he was appealing to the tastes of his time. Men of means would go on the ‘Grand Tour’, soaking up the sun-drenched marble remnants of Rome’s great Empire and mopping up fragments of ancient stone to place on pedestals in their stately homes. As Rome had conquered from Hadrian’s Wall to Egypt, Syria to Spain, so the British Empire was casting itself in its image as it spread ever further across the globe.

But the white-washed idealism of these English sculptures fundamentally misunderstood the exemplars they were mirroring. The originals were covered in colour! The fragments we see today – they’re just the skeletons of ancient monuments. Two millennia ago, the marble would have been covered with paint, features picked out as pink, rosy cheeks and red lips, costumes decorated in bright shades and details emphasised in a rainbow of colours.

This didn’t fit the post-reformation taste for stripped back church interiors. The plain marble sculptures of St Paul’s were not only a tasteful nod to a mis-imagined classical past, but a rejection of medieval Catholic England: a time of superstition, excess, popery and out-dated beliefs. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were a time of reason, where Britannia ruled the waves, and the great men of Empire were immortalised in pure, white stone.

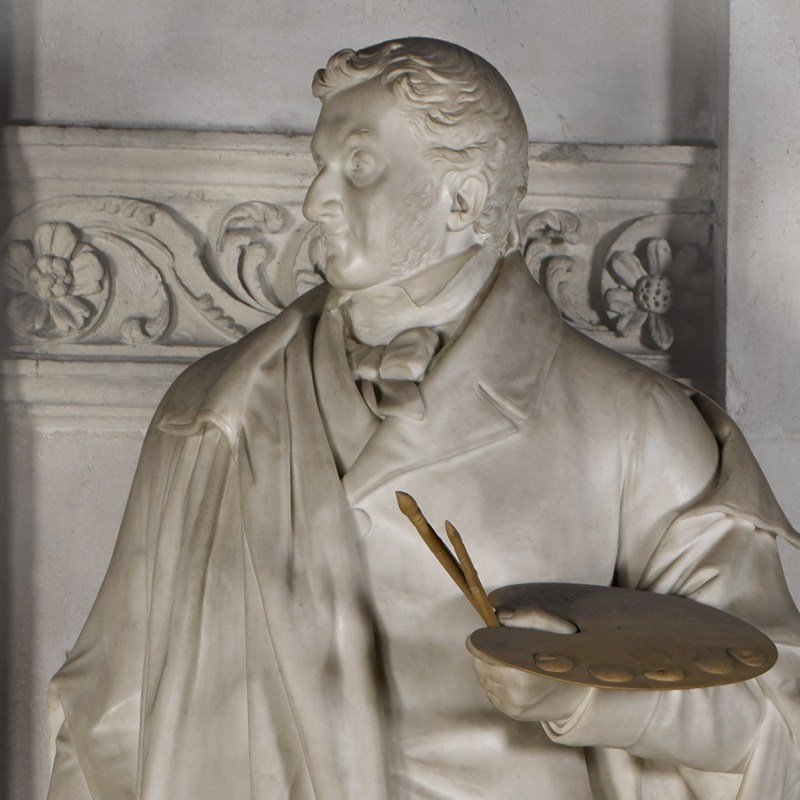

So, I turn to my favourite monument in St Paul’s. Tucked near the door in the south transept is an overly life-sized sculpture of J. M. W. Turner. It was created by Belfast-born sculptor Patrick MacDowell after Turner’s death in 1851. The master of colour, Turner looks thoughtfully at the sculptures around him. He leans back, taking in the scene, palette and brushes in hand. Behind his cloak, MacDowell has carved in low relief realistic looking seaweed, while at his feet is a starfish. Turner stands for eternity on England’s shoreline, looking to paint the beauty and colour of the natural world around him.

But what he gazes upon instead are monuments to the ocean-faring exploits of ‘great Britons’. Nelson’s victory at the Battle of Trafalgar is immortalised in stone, with the hero leaning on an anchor. Turner stares directly at another exuberant celebration of naval conquest, his eyeline meeting Earl Howe, Admiral of the Fleet until 1799. Britannia, complete with trident, toga and helmet, sits on a ship behind this great master of the seas.

Turner is an observer of these men of the past. Like his famous painting, The Fighting Temeraire, his monument captures a moment of change. Celebrated on every twenty-pound note today, Turner’s masterpiece shows a steam-powered tug pulling Nelson’s redundant tall ship to its retirement. The sun has set on the Age of Empire; make way for modernity. So Turner’s statue stands forever gazing on a period of English history that has passed. When his sculpture went up in the middle of the nineteenth century, the glory days of Nelson and Howe were fading. The tide was turning.

I think Turner would have been pleased with the positioning of his monument. As he documented the fading of empire in his life, so his sculpture, standing on an eternal stone sea front, remains a witness after death. But I wonder if he wouldn’t have liked more colour around him. He was an artist that captured the noise, steam and speed of the industrial revolution, and he’s remembered as the painter of light. His was a world steeped in colour.

His memorial reminds me that every generation rewrites the past in relation to their present. As I look on Turner’s monochromatic marble face, I see the vibrancy of his canvases and the colour he filled his life with. Today ours is a globally connected, high definition, colour saturated world. The white-washed faces of bygone days act as a reminder that we should celebrate the colour, variety and vibrancy around us today.

About Janina Ramirez

Dr Janina Ramirez is a cultural historian, broadcaster and author. She is a Research Fellow at Harris Manchester College, University of Oxford. She gained her PhD in ‘The Symbolic Life of Birds in Anglo-Saxon England’ at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York, where she remains an Honorary Fellow.

Nina has written a number of books, both fiction and non-fiction, including The Private Lives of Saints (2015), Julian of Norwich (2017) and The Viking Mystery series for OUP which won the Young Quills award in 2019. Her books Goddess: 50 Goddesses, Spirits, Saints and Other Female Figures Who Have Shaped Belief (illustrated by Sarah Walsh) and Femina: A New History of the Middle Ages will both be published in 2022. She has written and presented over thirty documentaries for BBC Four, including ‘The Hundred Years War’ and the Art Lovers’ Guide series, as well as, most recently, the BBC2 Raiders of the Lost Past. She has a popular podcast, The Art Detective, and is a regular contributor to television and radio, including ‘Front Row’ for Radio 4.

Visit Dr Janina Ramirez’s website and find her on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

About the Monument

The artist J. M. W. Turner died of cholera in 1851 at the age of 76. Acclaimed in his lifetime and recognised today as one of Britain’s greatest artists, Turner bequeathed a huge body of work to the Nation. He is buried, in accordance with his wishes, ‘amongst his brothers in art’ in the Artists’ Corner in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral. His monument in the south transept of St Paul’s was the first on the cathedral floor to an artist and was partly paid for by the £1000 he left in his will for his memorial. It was sculpted by Northern Irish sculptor Patrick MacDowell RA (1799 – 1870) and installed in 1855.